In our latest guest post, Jane Gray, Professor of Sociology at Maynooth University, Ireland, focuses on reconciling different temporalities when bringing together a data set comprising retrospective life story narratives with a set of qualitative longitudinal interviews from a prospective panel study.

In our latest guest post, Jane Gray, Professor of Sociology at Maynooth University, Ireland, focuses on reconciling different temporalities when bringing together a data set comprising retrospective life story narratives with a set of qualitative longitudinal interviews from a prospective panel study.

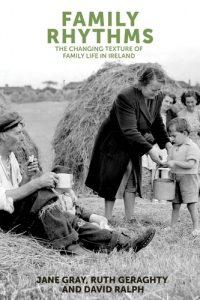

Jane has expertise in families, households and social change, as well as qualitative data management and sharing. She has completed studies such as Family Rhythms using archived data sets. She has contributed to the development of the Digital Repository of Ireland and is the programme leader for the Irish Qualitative Data Archive.

Working backwards and forwards across the data: Bringing together qualitative longitudinal datasets with different temporal gazes

Bren Neale (2019, p. 20) has contrasted qualitative longitudinal (QLR) methods that prospectively trace lives  through time with approaches to the study of lives that reconstruct them through a retrospective gaze. Joanne Bornat and Bill Bytheway (2012) showed how different methods of data collection construct different temporalities within QLR. In this blog post I describe how the Family Rhythms project created an interesting opportunity to bring different temporal gazes and temporalities together, in a study funded by the Irish Research Council as a demonstrator project for secondary qualitative data analysis in Ireland. Inspired by new sociological approaches to understanding family life as configurations, practices and displays, Ruth Geraghty, David Ralph and I aimed to develop a fresh understanding of long-term patterns of family change by bringing retrospective life story narratives from the ‘Life Histories and Social Change’ (LHSC) project together with qualitative interviews collected as part of the first wave of the prospective panel study ‘Growing Up in Ireland’ (GUI).

through time with approaches to the study of lives that reconstruct them through a retrospective gaze. Joanne Bornat and Bill Bytheway (2012) showed how different methods of data collection construct different temporalities within QLR. In this blog post I describe how the Family Rhythms project created an interesting opportunity to bring different temporal gazes and temporalities together, in a study funded by the Irish Research Council as a demonstrator project for secondary qualitative data analysis in Ireland. Inspired by new sociological approaches to understanding family life as configurations, practices and displays, Ruth Geraghty, David Ralph and I aimed to develop a fresh understanding of long-term patterns of family change by bringing retrospective life story narratives from the ‘Life Histories and Social Change’ (LHSC) project together with qualitative interviews collected as part of the first wave of the prospective panel study ‘Growing Up in Ireland’ (GUI).

Because the LHSC study was carried out with three birth cohorts of Irish people (born before 1935, 1945-54 and 1965-74), we initially aimed to treat the GUI interviews (carried out with nine-year old children and their parents) as a fourth cohort (born around 1998). However, we soon found that the different study designs created challenges for this simple ‘additive’ approach. First, while the LHSC study included a life history calendar instrument to collect retrospective data about the timing of events in participants’ lives, the life story interviews were relatively unstructured, loosely guided by topic and life stage. By contrast, the GUI interviews were semi-structured with questions designed to map on to the broad themes covered within the quantitative panel study. More significantly, however, it soon became apparent that the different temporal gazes adopted within the studies affected the substantive content of the data. With their focus on remembering past events, the LHSC interviews (including the formal calendar) look ‘backwards’, whereas the GUI interviews have a pronounced ‘forward-looking’ focus on the children’s anticipated futures. This was reinforced, in the case of GUI, by additional instruments including, for example, an essay writing exercise that invited the children to imagine what their lives would be like at age 13. These divergent temporal perspectives affected how people talked about their family lives. While the LHSC interviewees ‘made sense’ of their family lives by reconstructing them within a biography, the GUI interviewees situated them within everyday practices and contemporary relationships. Their temporal orientation is anticipatory and aspirational, rather than reconstructive and explanatory.

Of course, these differences were not absolute: many LHSC interviews include narrative segments about hopes for the future, while some GUI parent interviews include reflections on past family lives. Nevertheless, the divergent temporal perspectives of the studies meant that it was not possible to make straightforward thematic or life stage comparisons across cohorts. We addressed this challenge by adopting a ‘temporal gaze’ within our analysis, in a process that we have described as ‘working backwards and forwards across the data’ (see Gray, Geraghty and Ralph 2013; Geraghty and Gray 2017). In effect, this meant that we read both with and against the temporal ‘grain’ of the data (Savage 2005), often incorporating different generational standpoints. This can be seen most clearly in our analysis of the changing relationship between grandchildren and their grandparents. A reading that begins with children in the GUI study and works backwards across LHSC participants’ childhood memories, reveals an exceptional degree of continuity in the quality of the relationship from the perspective of grandchildren, going right back to the earliest decades of the 20th century. However, a reading that begins with the childhood memories of the oldest LHSC participants and works forwards through memories and contemporary experiences from the perspectives of parents and grandparents, reveals significant change in the family, household and community contexts within which the grandchild-grandparent relationship was experienced across historical time. This analytical approach thus yielded new substantive and theoretical insights on the character of long-term patterns of family change.

Our strategy of ‘reading backwards and forwards’ emerged as a way of addressing the challenges presented by our efforts to work across qualitative longitudinal datasets with different temporal gazes and temporalities. However, what started out as a problem turned into an opportunity to develop higher level understandings of long-term patterns of family change by reading with and against the temporal grain of the datasets, illustrating the potential for including divergent temporal gazes within the corpus of QLR.

References

Bornat, J. and Bytheway, B. (2012) Working with different temporalities: Archived life history interviews and diaries. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(4): 291-299.

Geraghty, R. and Gray, J. (2017) Family Rhythms: Re-visioning family change in Ireland using qualitative archived data from Growing Up in Ireland and Life Histories and Social Change. Irish Journal of Sociology, 25(2): 207-213.

Gray, J., Geraghty, R. and Ralph, D. (2013) Young grandchildren and their grandparents: continuity and change across four birth cohorts. Families, Relationships and Societies, (2)2: 289-298.

Neale, B. (2019). What is Qualitative Longitudinal Research? London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Savage, M. (2005). Revisiting classic qualitative studies. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 118-139.