Our guest post today is by Sue Bellass, a PhD student in the School of Nursing, Midwifery, Social Work and Social Sciences at the University of Salford. Her thesis, which she is due to submit in August, has been exploring how intergenerational families are affected by young onset dementia over time.

Our guest post today is by Sue Bellass, a PhD student in the School of Nursing, Midwifery, Social Work and Social Sciences at the University of Salford. Her thesis, which she is due to submit in August, has been exploring how intergenerational families are affected by young onset dementia over time.

In this post, Sue shares in detail her approach to analysing data over time, from multiple perspectives. The process has been complex and challenging, but has also brought creativity and freedom – and ultimately a deeper understanding of the lived experience of young onset dementia.

If you would like to know more about Sue’s research, contact her by email: s.bellass@edu.salford.ac.uk.

The challenges of multiple perspectival qualitative longitudinal (QL) analysis: a strategy created for an intergenerational study of young onset dementia

Although dementia is often perceived to be a condition that occurs in later life, around 1 in 20 people with dementia are below the age of 65 (Alzheimer’s Society, 2015). Over the last two decades there has been increasing interest in developing qualitative understandings of the experience of the condition in younger people; however, almost without exception existing studies have used cross-sectional designs, providing only a snapshot of life with an unpredictable, dynamic condition. For my PhD I decided to use a QL methodology to explore relationality over a twelve-month period by following five intergenerational families where one person had received a diagnosis of young onset dementia.

Since people with dementia are a marginalised, negatively positioned group (Sabat et al., 2011), I felt it was appropriate to democratise the research process to enable my participants to choose their preferred means of engaging with the study. This choice included the method of data collection (ethical approval was gained for interviews, audio/ video diaries, blogs and tweets) and, if participants opted for interviews, which family members would participate and where the interviews would take place. Ultimately, 18 participants chose to be interviewed, 16 of whom were interviewed in pairs or larger family groups, with two preferring individual interviews. Interviews were conducted in three waves at months 0, 6 and 12.

Analysing the data set has been a challenging process. As Henderson et al. (2012) note, despite increasing interest in QL methods, methods of analysing and representing complex QL data sets have rarely been explicated. I experienced this as a mixed blessing; on the one hand, there is space for creativity, flexibility and freedom, on the other, there is room for doubt to flourish! I have attempted to slice the data in different ways in order to interrogate the data set to best effect. Inspired by Thomson (2010, 2014), I treated each family as a unique case and also aimed to create a cross-case analysis across the four generations represented in the families.

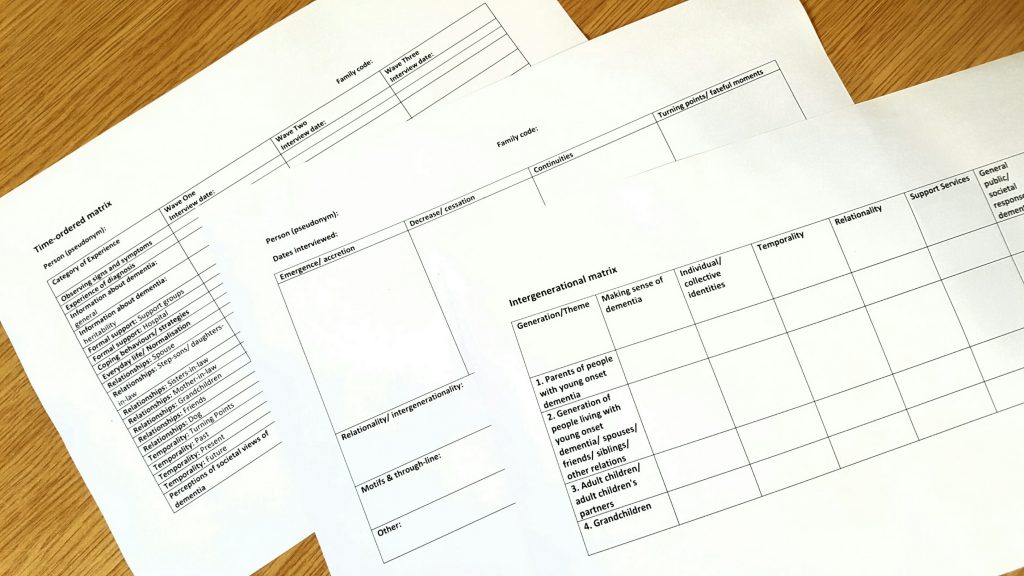

Example QL matrices

Initially I attempted to analyse the group interviews at the ‘family’ level, however it quickly became apparent that divergent accounts were being obscured. Subsequently I took a multiple perspectival approach (Ribbens McCarthy et al., 2003), teasing apart individual experiences within the families, viewing them as cases within a case. For each person, I induced categories of experience then, to permit holistic re-engagement, organised the raw data in a time-ordered matrix across the three waves.

Then, again for each person, I created a longitudinal matrix adapted from Saldana (2003) to look for transitions and continuities, using motif coding, a form of coding which draws attention to recurring elements in experiences, and describing through-lines, a crystallisation of a participant’s change over time. Although it could be argued that such an approach may disguise intersubjective creation of meaning, I consciously retained a focus on relationality, creating spaces within the matrix to capture data on meaning-making processes over time. Finally I created an intergenerational matrix, organising the data by generation to look for patterns and themes, setting the data against the backdrop of the recent increasing public, policy and research interest in dementia to try and interweave biographical, generational and historical timescapes.

Qualitative research has faced criticism for lack of clarity regarding the relationship between theory and data, and this, I argue, is an important area to address as we continue to develop the contours of QL research. My own perspective has been influenced by Mills (1959), who describes a ‘shuttle back and forth’ between theory and data. I have utilised such an iterative approach, and have drawn on theory from the sociology of chronic illness and family and relationship sociology to develop understandings of the intergenerational experience of young onset dementia.

References:

Alzheimer’s Society (2015). Dementia 2015: Aiming higher to transform lives. London: Alzheimer’s Society.

Henderson, S., Holland, J., McGrellis, S., Sharpe, S., & Thomson, R. (2012). Storying qualitative longitudinal research: sequence, voice and motif. Qualitative Research, 12(1), 16-34.

Mills, C.W. (1959). The sociological imagination. London: Penguin.

Ribbens McCarthy, J., Holland, J., & Gillies, V. (2003). Multiple perspectives on the ‘family’ lives of young people: methodological and theoretical issues in case study research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 6(1), 1-23.

Sabat, S.R., Johnson, A., Swarbrick, C., & Keady, J. (2011). The ‘demented other’ or simply ‘a person’? Extending the philosophical discourse of Naue and Kroll through the situated self. Nursing Philosophy, 12(4), 282-292.

Saldaña, J. (2003). Longitudinal qualitative research: analyzing change through time. California: Alta Mira Press.

Thomson, R. (2010). Creating family case histories: subjects, selves and family dynamics. In Thomson, R. (Ed.) Intensity and insight: qualitative longitudinal methods as a route to the psycho-social. Timescapes Working Paper Series No.3.